Collective Threads: A Public Presence is a community project culminating in a powerful new exhibition by award-winning artist Kathrin Longhurst, launching during Refugee Week 2025. Through large-scale figurative portraiture and an immersive video installation, the project centres the voices of Iranian-Australian women and LGBTQI+ individuals who have faced censorship, displacement, and gender-based persecution. At a time when human rights and gender equity remain under siege globally, the exhibition invites audiences to consider whether oppression is bound by geography - and what it means to belong in public space.

Bringing together over a dozen collaborators – visual artists, musicians, activists, advocates, and filmmakers – Collective Threads is both a creative act and a political statement. The exhibition reclaims propaganda aesthetics to challenge patriarchal narratives, pairing monumental paintings with spoken-word performances and bilingual video works in English and Farsi. These deeply personal testimonials, produced with Kurdish Iranian filmmakers, offer a blueprint for solidarity and healing that resonates far beyond the gallery. Live events will extend the work into the community, creating space for dialogue around feminism, migration, and cultural identity.

This website is a dedicated media resource for the exhibition. Here, you can access the images, video previews, artist and participant info, and downloadable materials. For interview requests, media tours, and event coverage opportunities, please visit our Contact section to contact us directly. Collective Threads is more than an exhibition—it’s a timely conversation starter with global relevance and local urgency.

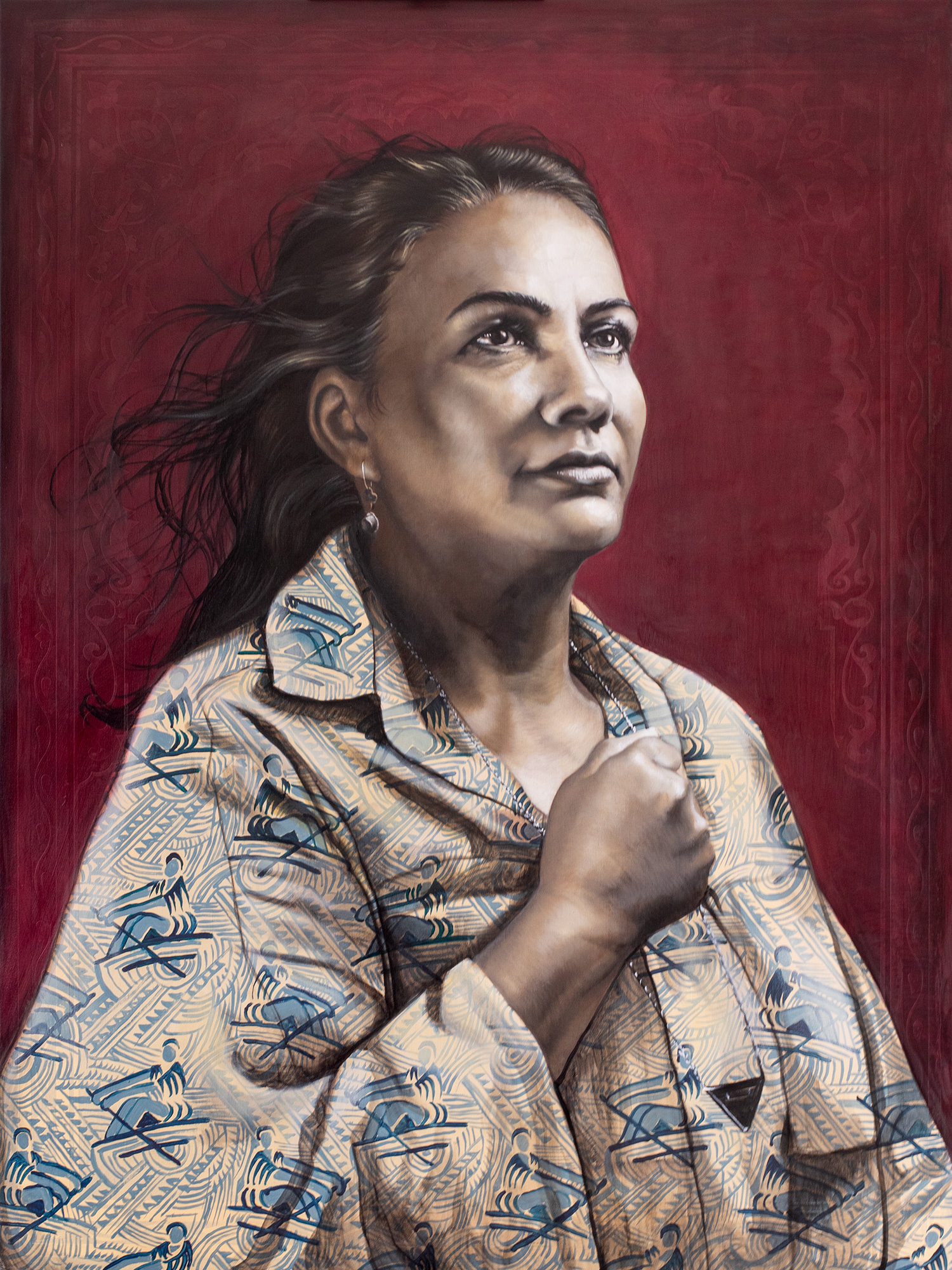

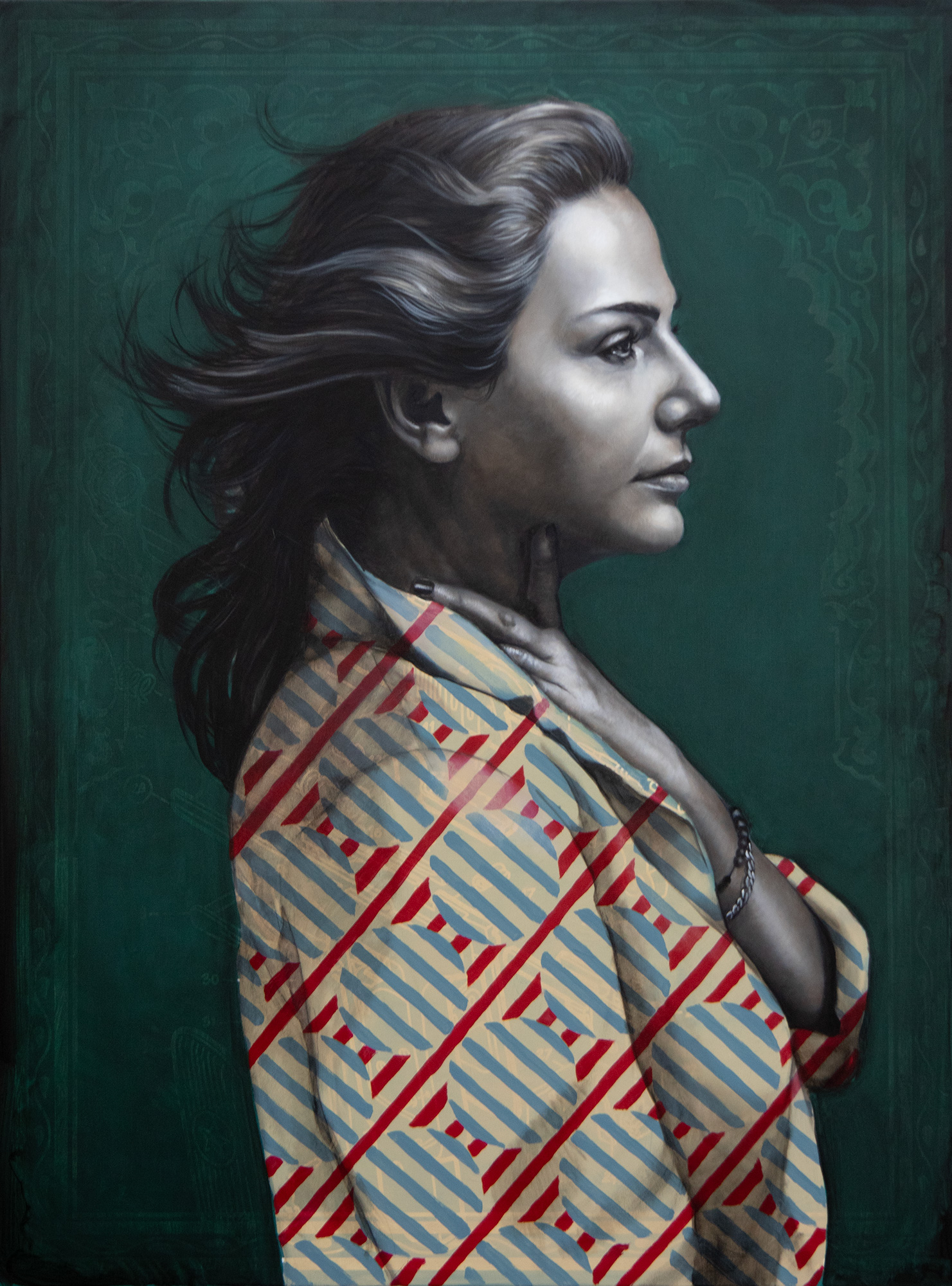

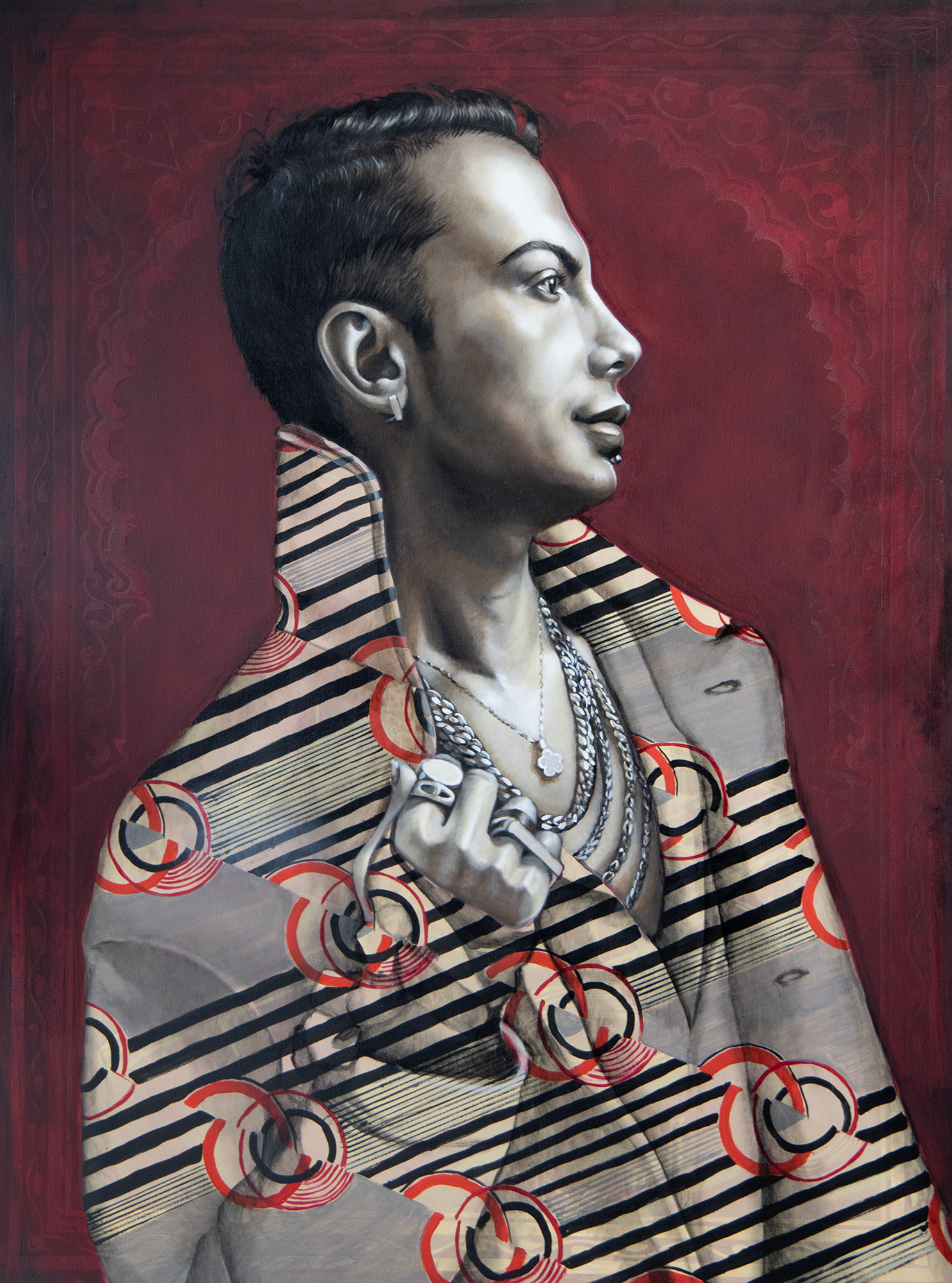

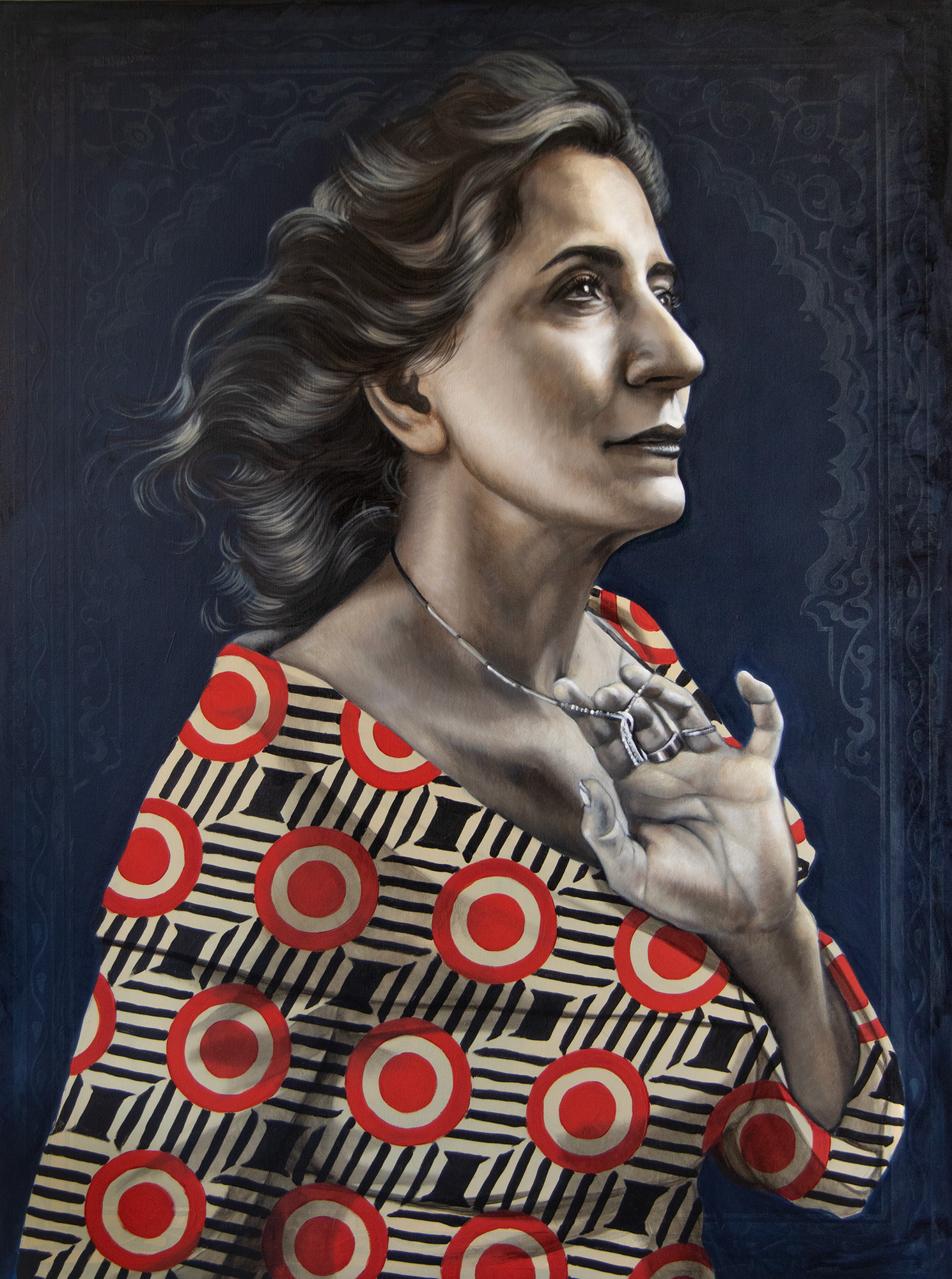

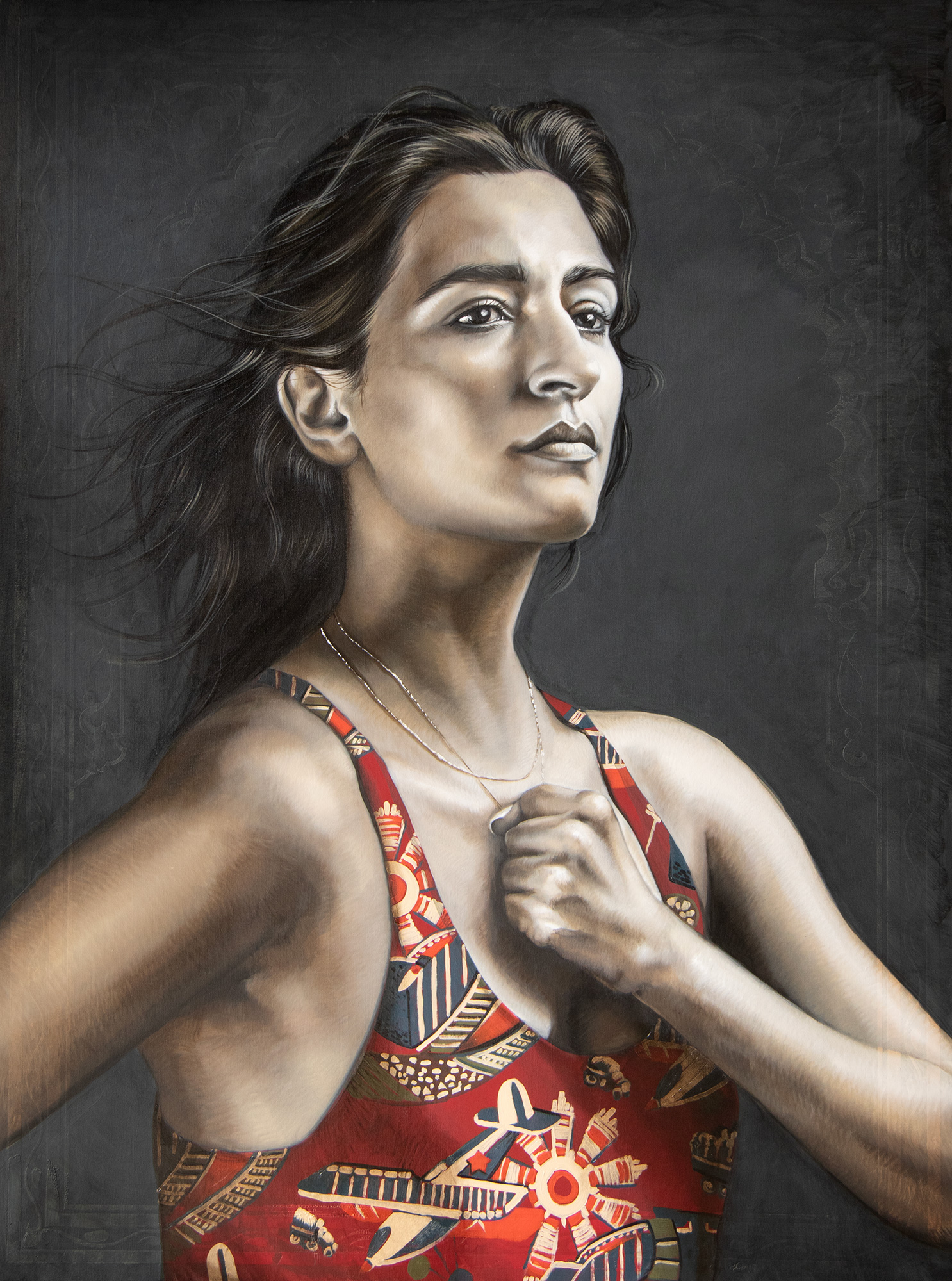

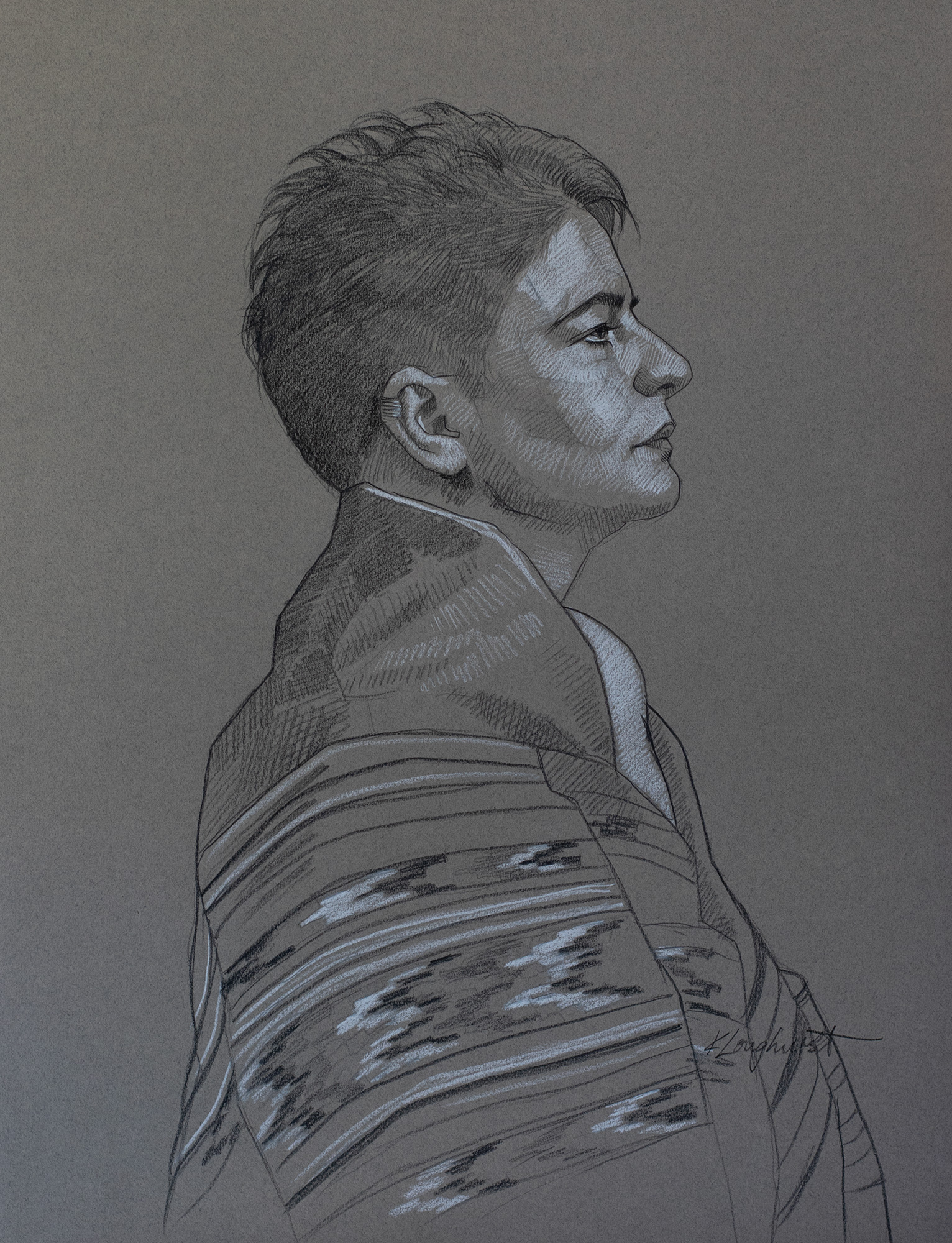

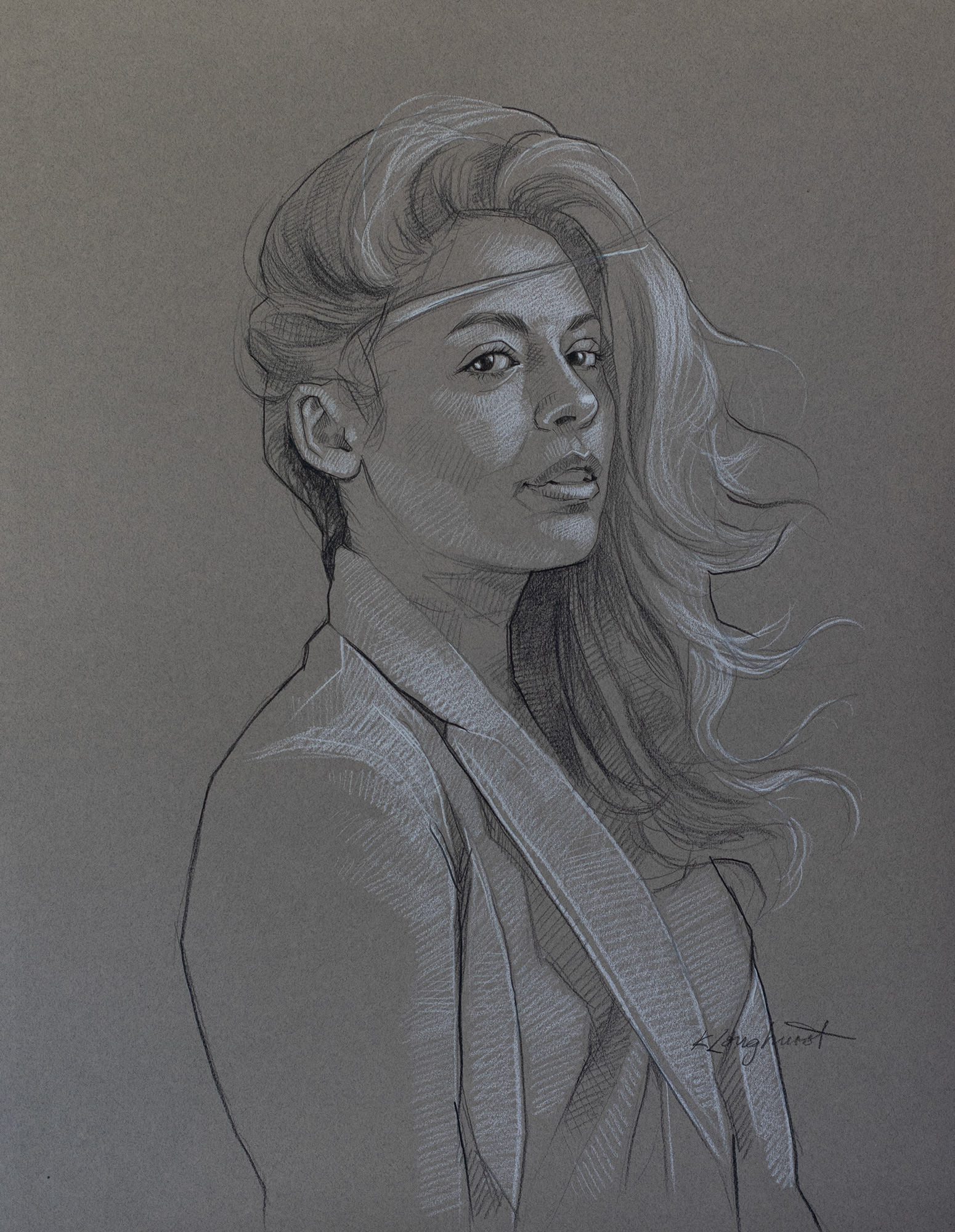

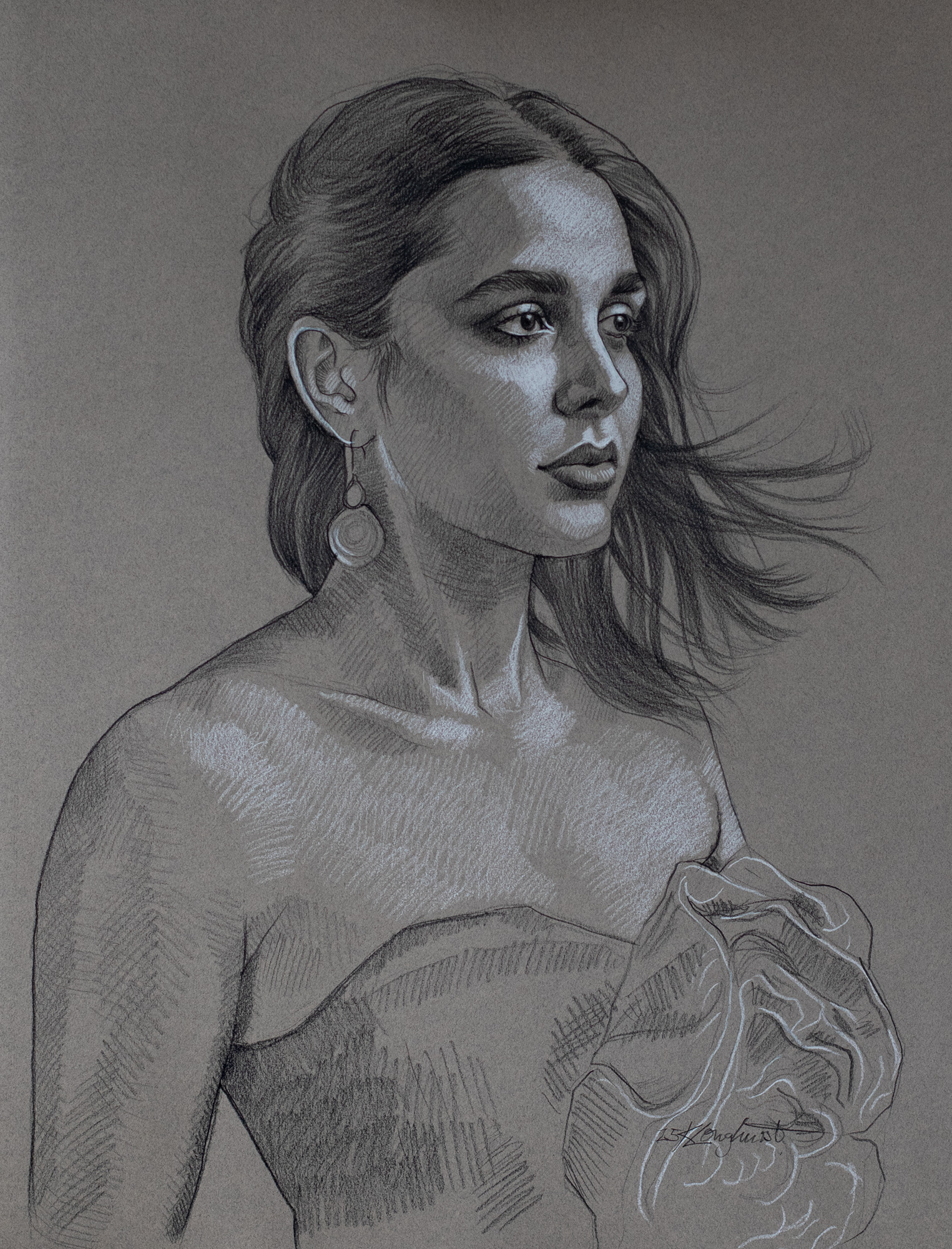

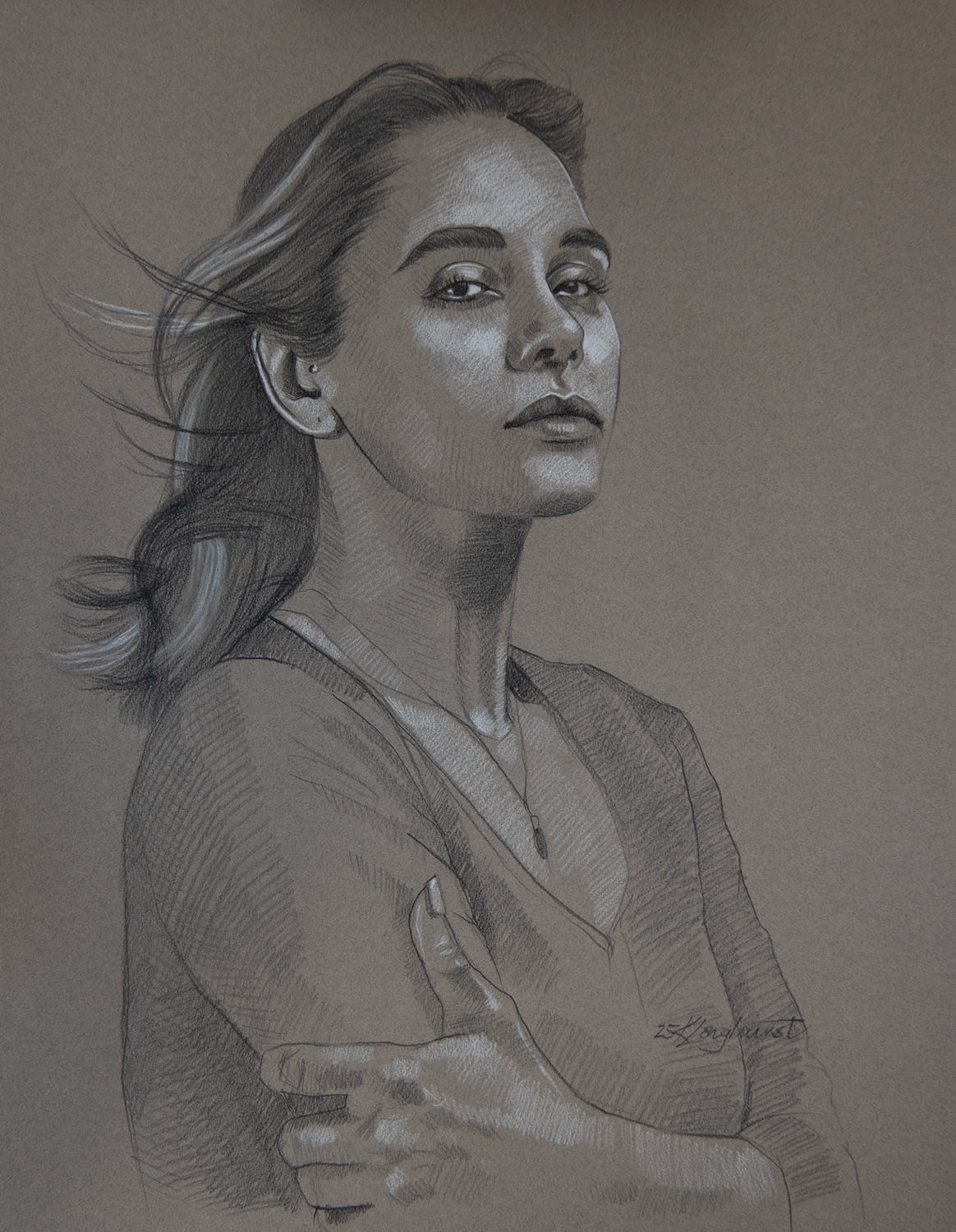

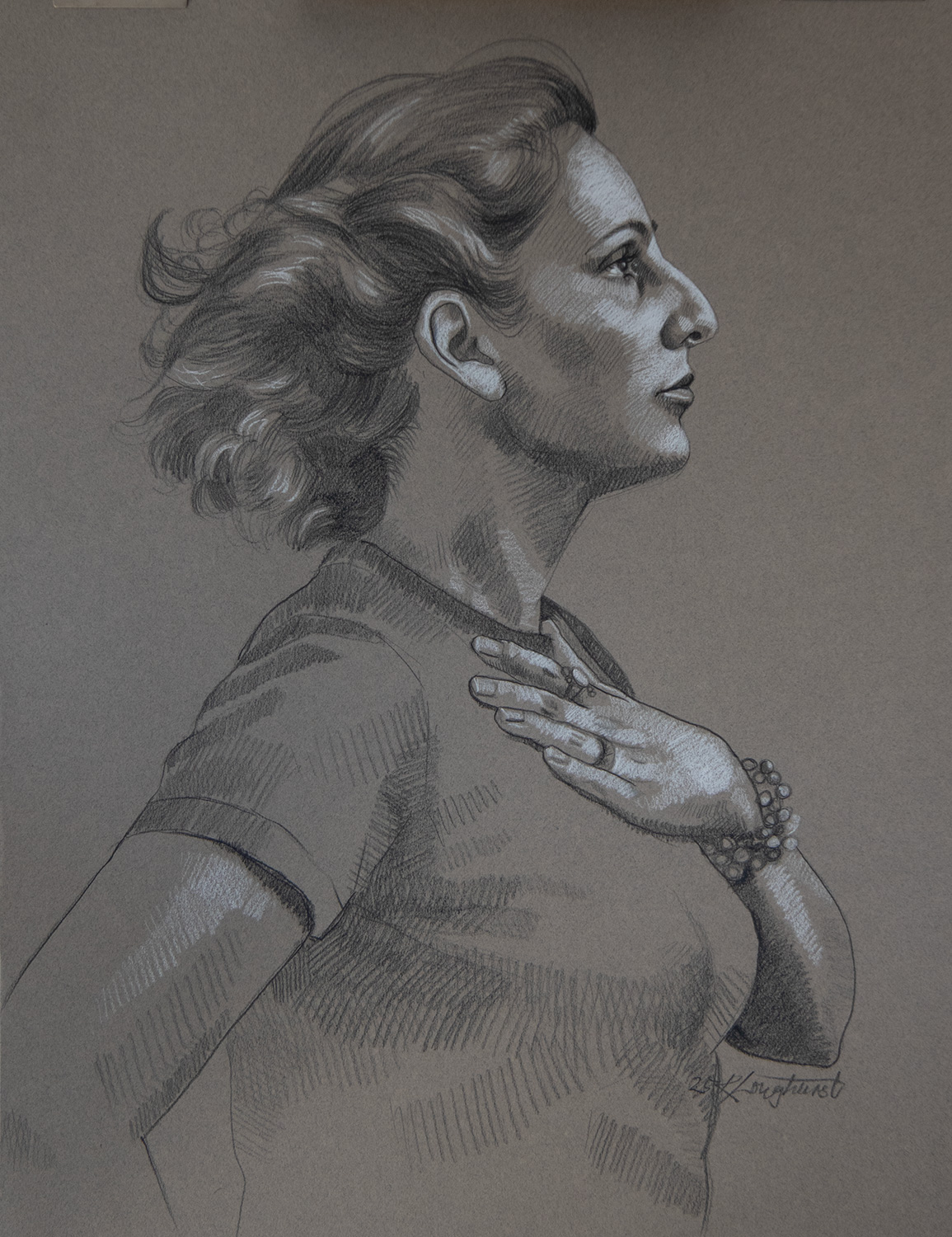

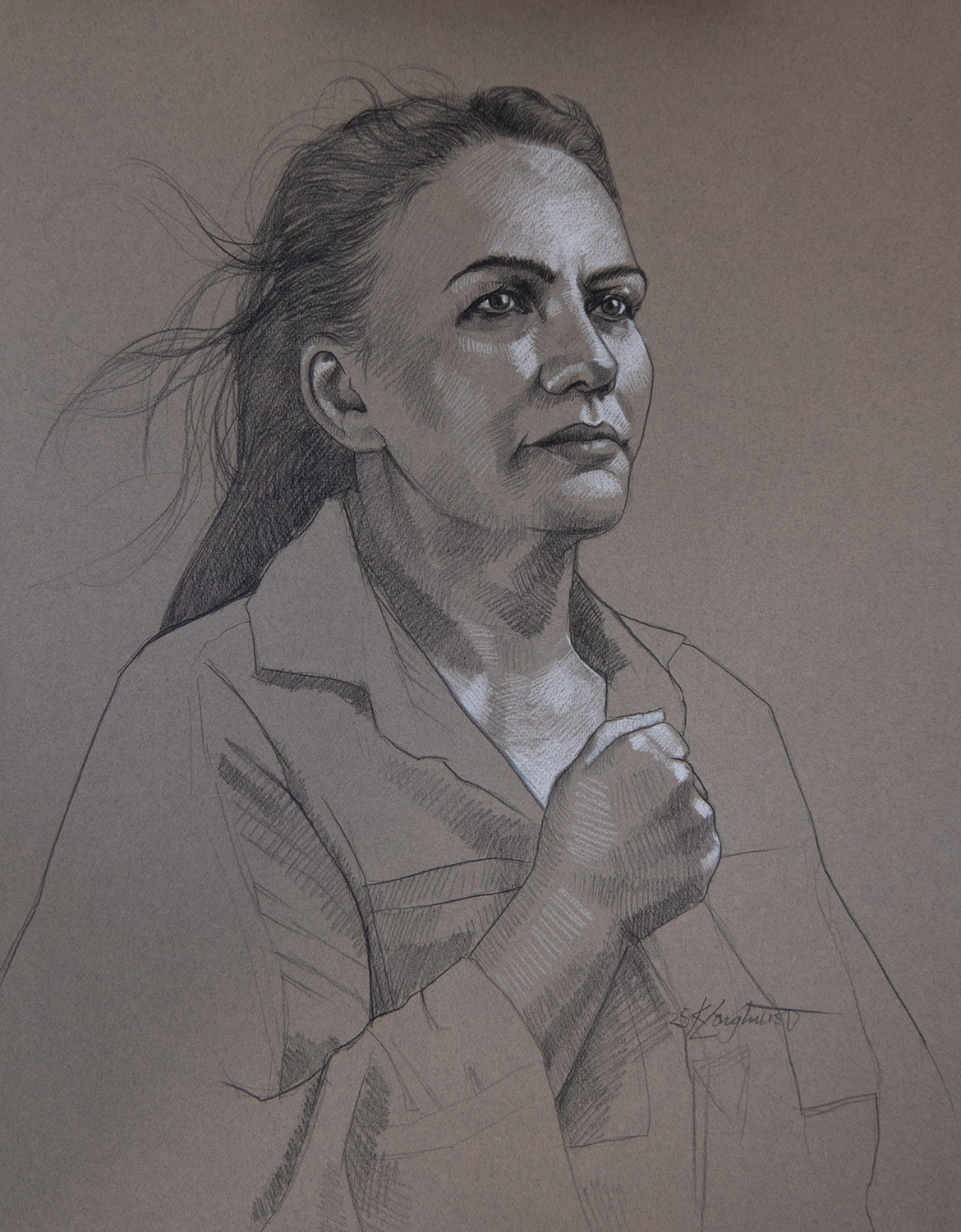

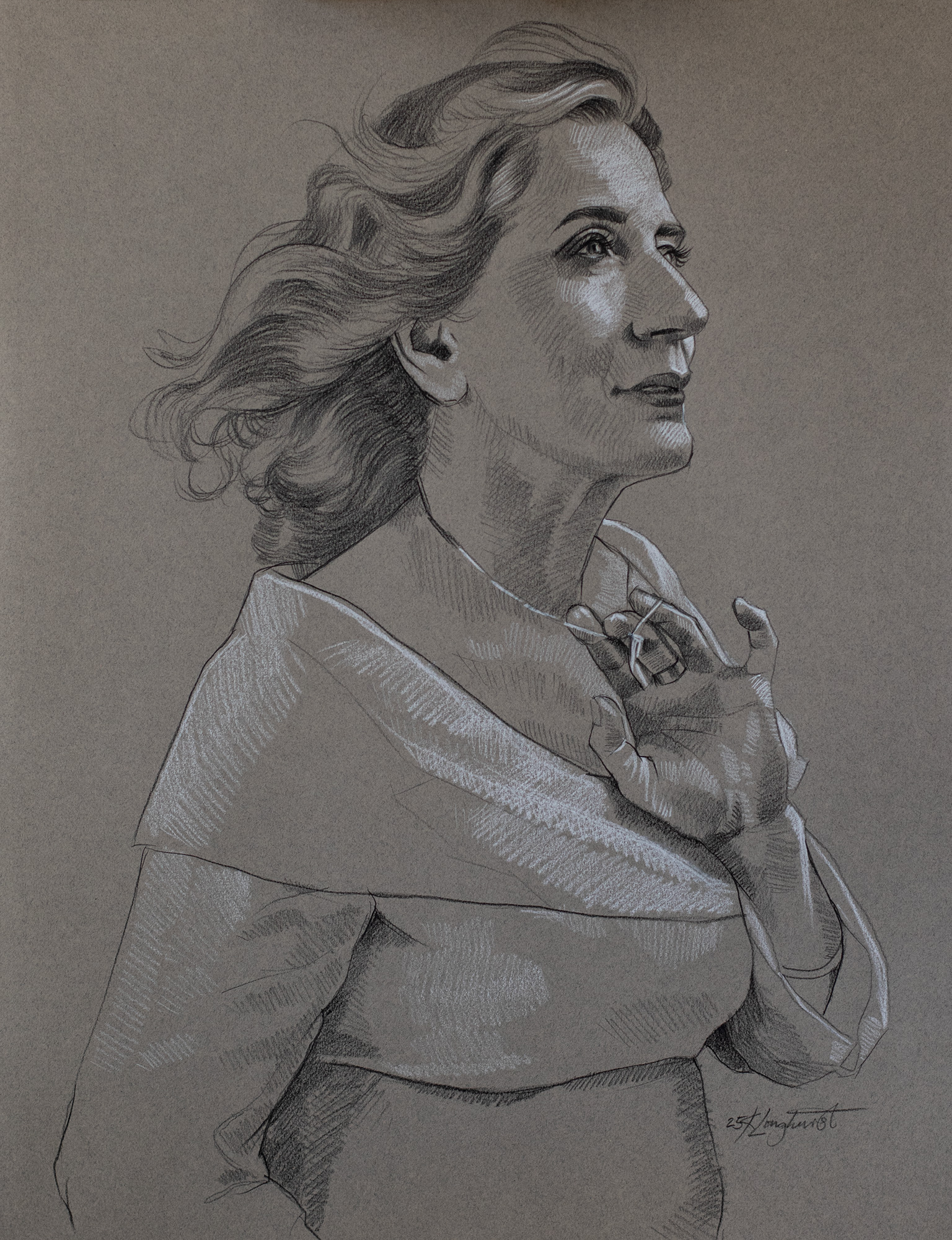

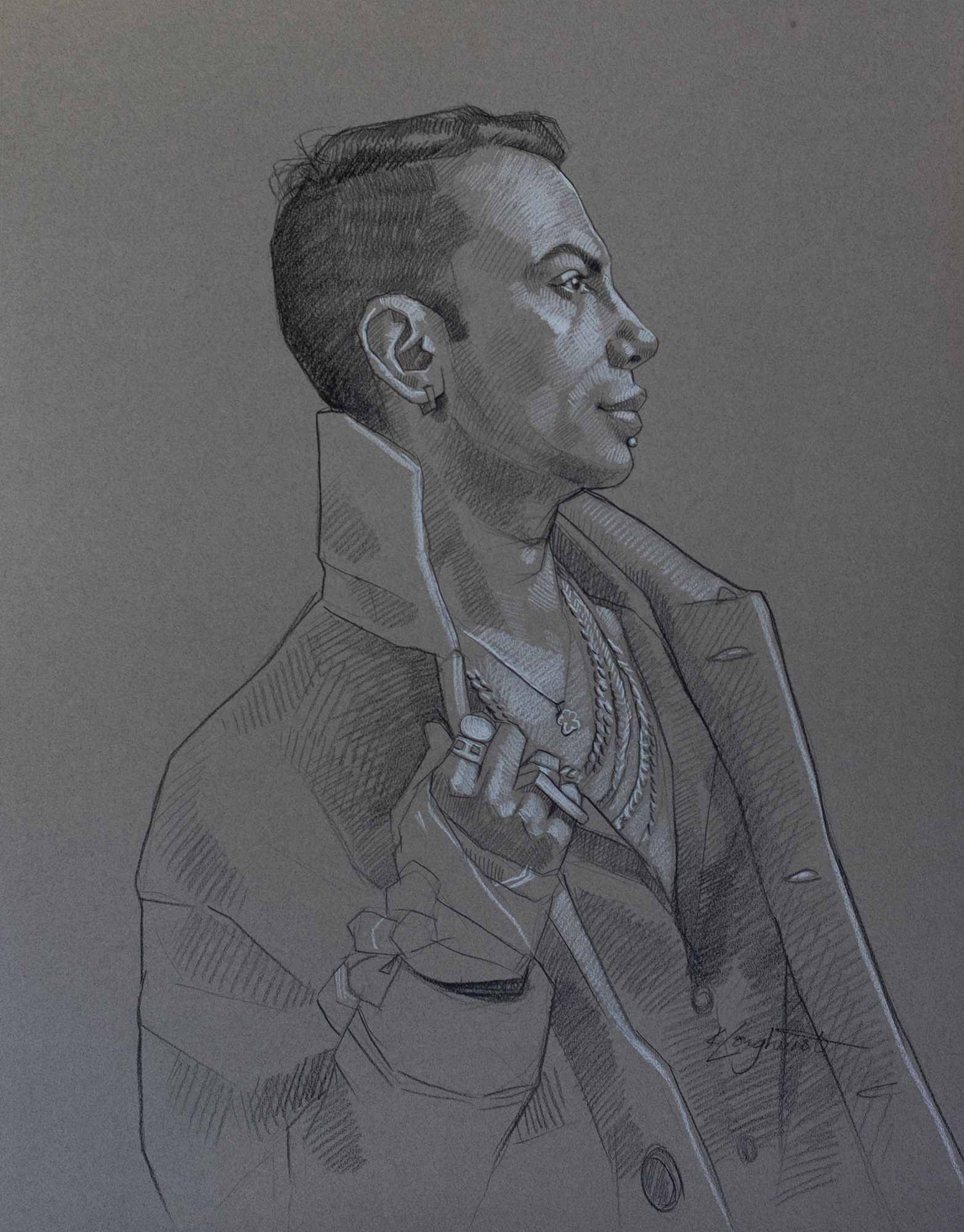

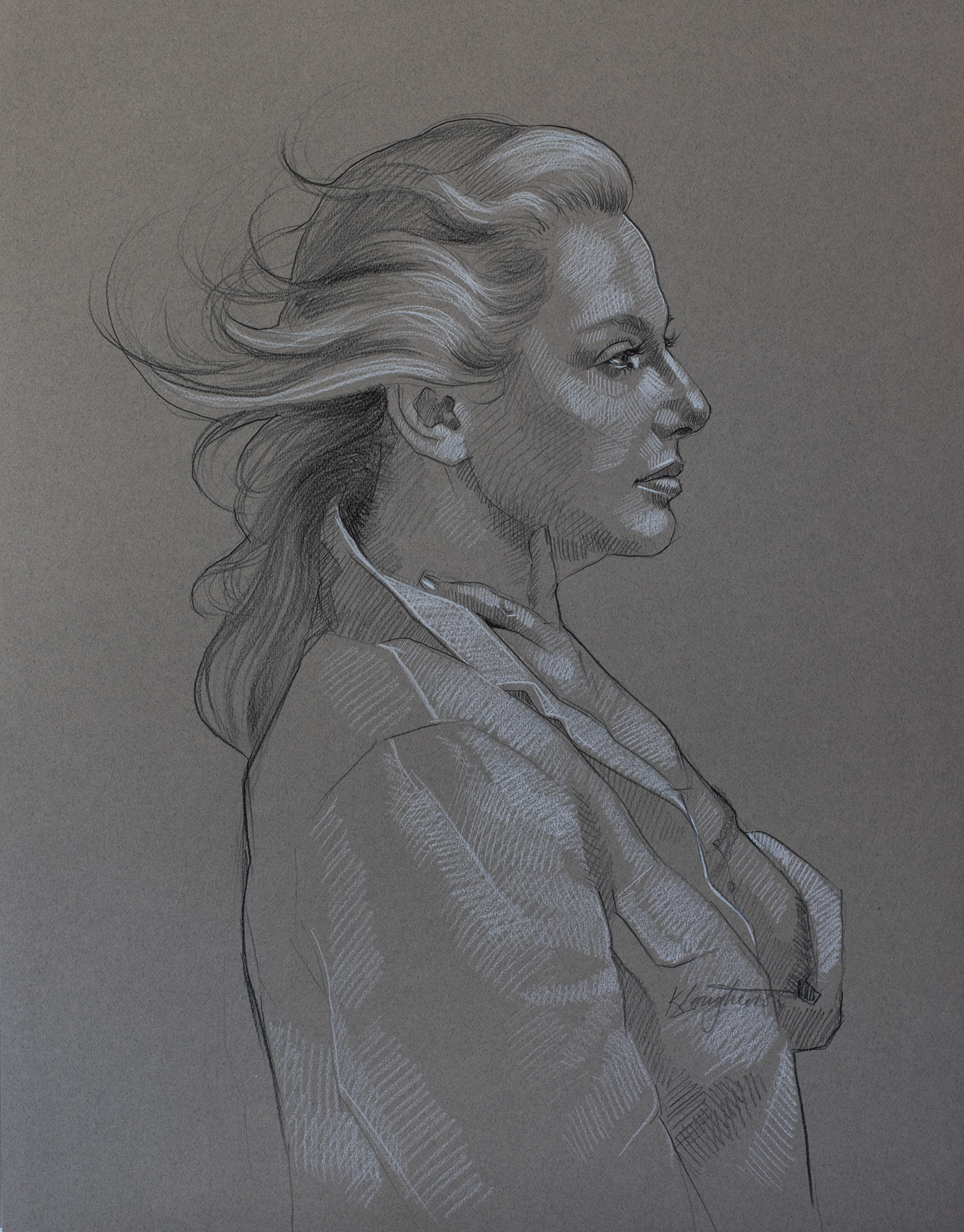

Paintings by Kathrin Longhurst

Behind the Scenes

Please contact us if you require the high resolution photos via the contact form below.

Photography by L.R.P. Productions

The Exhibition Essay by Joey Hespe

Collective Threads is not a quiet exhibition. It does not ask permission, nor does it whisper or wait to be invited in. Instead, it demands to be seen and heard. Loudly, fiercely, and without apology. Through film, painting and poetry Collective Threads confronts with presence, resistance, and memory.

This exhibition does not seek to condemn, but to expose. Nor just to represent, but to reclaim. It lays bare the mechanisms by which voice, agency, and opportunity have been stripped from those living under oppressive regimes. Longhurst unearths the silence buried beneath generations of docility, not to speak for others, but to amplify those already screaming. In her hands, the female form is not rendered as muse or myth, but as a monument to survival. She compels us to confront what feminist scholar Sara Ahmed terms “the affective politics of the body” (Ahmed, 2004). A body that remembers, resists, and revolts.

As Longhurst herself acknowledges, the message for this exhibition is from an outsider’s perspective, one filtered through a Western lens. She is not Iranian. She is not living that reality. But she knows censorship. She lived it in East Berlin under Stasi surveillance, and she knows the danger of silence. Her work is not about speaking for others, but instead, she allows space to amplify the voices that are waiting to be heard. Voices that are screaming.

Collective Threads challenges a tradition in which the female form has historically served as muse rather than maker. In the canon of Western art, women have been confined to what Laura Mulvey describes as “to-be-looked-at-ness” (Mulvey, 1975), their function primarily ornamental, their value tethered to male genius–to the male gaze. Collective Threads tears through this legacy. In Longhurst’s paintings, the sitters meet the viewer’s gaze head-on. Stoic, burning, unflinching. The embossing patterns that frame each of the subjects reference Persian wedding invitations. Typically ornate, celebratory, and decorative, these designs become symbols of entrapment. Their visual beauty masks their purpose: to signify the binding of a woman into a life not always of her choosing. The homage to Russian Constructivist patterns, meanwhile, recall women like Liubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova, artists whose creative contributions were subsumed into the machinery of political propaganda. Despite their radical innovations, they became cogs in state-controlled collectives, their artistic legacies eclipsed by male counterparts. Longhurst weaves these histories into her portraits, refusing the erasure of women’s labour, both past and present.

The danger, as many feminists have long argued, lies not just in authoritarian governments but in forgetting. The independent Kurdish film crew who are documenting this project, that shares the title name of this exhibition, reminds us that in the 1970s, Iranian women were among the most liberated in the region. Today, that memory has been strategically erased. Now, under theocratic rule, many women must seek permission from their husbands to leave the house, drive a car, or even meet a friend for a coffee. Things we take for granted in the West. This regression is not incidental. It is weaponised gender control. But it is not just women who face oppressive rule. Longhurst’s representation of Hamed,shows how LGBTQIA+ people face the same repressed conditions to women in Iran. As feminist theorist Judith Butler suggests, power operates not only through law, but through the daily disciplining of bodies (Butler, 1993). Longhurst offers a direct confrontation with that conditioning, refusing this disciplining gaze – giving posture and defiance to those reduced to silence.

In Longhurst’s film, these voices, recorded and amplified, resist erasure. The sitters are positioned in circular formation–a contemporary reimagining of the women’s circle, passing strength from one to the next, like a living chain of resistance. One woman, Nazanin Jebeli, recites a poem she created while trying to flee her country: “I’ve been trapped in the longest autumn of my life… never mind, spring is coming.” It is this spirit, defiant, poetic, impossible to kill, that defines the spirit of Collective Threads.

But this exhibition is not limited to Iran. The digital age has collapsed borders. As Longhurst asks through her work: if persecution is not bound by geography, how can we pretend we are separate? In Australia, the supposed “safe haven,” more women are being killed by male violence year on year. Misogynistic ideologies once confined to fringe groups have been mainstreamed through ‘podcast bros’ and the manosphere’s backlash to #MeToo. Young men are being radicalised online at alarming rates, rebranding sexism through soft-boy charm: “She doesn’t have to work if she doesn’t want to,” they say. “She should just go on a hot girl walk and smile when she gets home.” Western culture has long disciplined women’s bodies through cultural norms, ideals, and practices that maintain patriarchal control (Bordo, 1993). These scripts are not harmless. They are insidious. They shape a culture where women’s autonomy is undermined in ever more subtle, patronising forms of micro-sexism.

In this context, Collective Threads functions as both a spotlight and a mirror. It illuminates the violence happening abroad, but also reflects the systemic misogyny embedded at home. As feminist scholar Sara Ahmed writes, “feminism is an archive of survival” (Ahmed, 2017). Longhurst curates such an archive, built not from artifacts of trauma, but from expressions of refusal.

Longhurst is not just painting portraits; she is painting survival, defiance, lineage. The figures she renders are not muses, they are monuments. And like monuments, they demand remembrance. They stand for the artists erased from the record, the women forced to whisper their truths, and the mothers, daughters, sisters, and LGBTQIA+ people who continue to be denied basic rights in every corner of the globe. This is not an exhibition about a distant, exoticised “elsewhere.” This is a reckoning with our shared now.

Joey Hespe.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press, 2017.

- Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. University of California Press, 1993.

- Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. Routledge, 1993.

- Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6–18.

- Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTnews, January 1971.